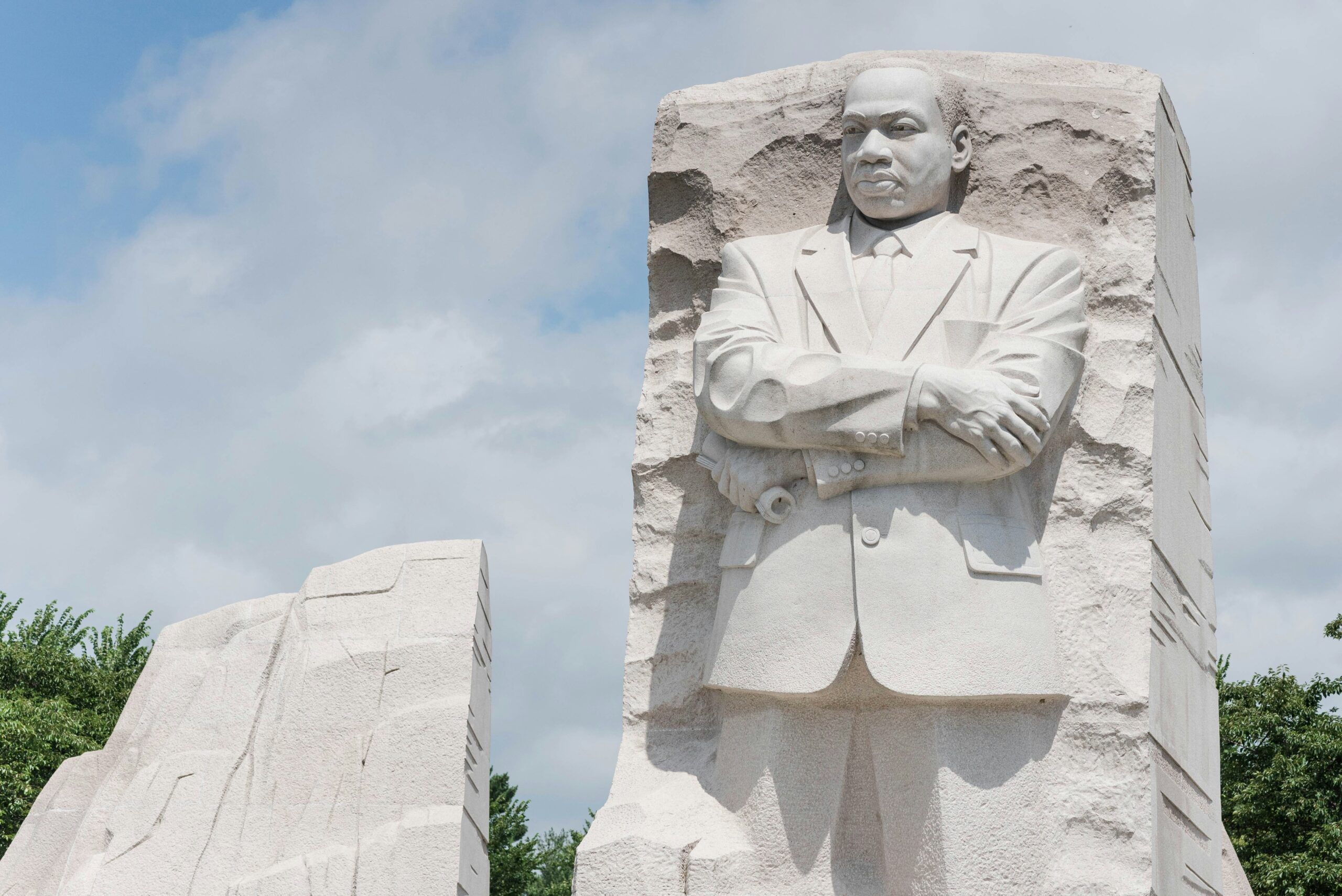

Honoring Dr. King’s Legacy: Inspiring Words for Today and Every Day

Happy Martin Luther King Jr. Day!

Dr. King’s words have always been a source of inspiration to many. Even though they were written decades ago, they continue to resonate deeply and remind us of the power we all have to make the world a better place.

One of Dr. King’s most impactful writings, Letter from Birmingham Jail, was penned in 1963 while he was imprisoned for participating in nonviolent protests against segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. In the letter, King responds to criticisms from local clergymen who called his actions “unwise and untimely.” Rather than retreating, Dr. King used the opportunity to explain why he felt it was not only necessary but urgent to fight for justice. Though his words were shaped by the challenges of his time, they still hold incredible relevance today.

This year, as we honor Dr. King’s legacy, we took some time to revisit this powerful letter. It’s not an easy read. It’s a letter born of frustration, written in the face of incredible injustice. But it’s also a letter filled with hope, resilience, and a call to action that still rings true today.

There were a few quotes that stopped us in our tracks as we read, and we wanted to share them with you—not just for what they meant then, but for what they can mean to us now.

“Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is injust. Segregation…substitutes an “I it” relationship for an “I thou” relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.”

This line reminded us of how easy it can be to lose sight of someone’s humanity. It’s something we see every day, whether in the rush of our busy lives or in moments of conflict and misunderstanding. Dr. King’s words challenge us to slow down, to really see the people around us—not just as roles or labels, but as individuals with their own stories, struggles, and dreams. Small acts of kindness, even something as simple as a smile or a kind word, can remind someone (and ourselves) of that shared humanity.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”

This is such a powerful reminder of how connected we are. When someone in our community is struggling, it isn’t just their burden—it’s something that ripples out and affects us all. But the same is true of hope and kindness. When we choose to lift each other up, those small actions can grow into something much bigger. They create a ripple effect that brings us all closer together and makes our communities stronger.

“So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the perseveration of injustice or for the extension of justice?”

This quote makes us pause and reflect on the importance of taking a stand for our values. Dr. King wasn’t advocating for division or conflict; he was challenging us to think deeply about what matters most to us. It’s easy to stay neutral, to avoid uncomfortable conversations or hard decisions—but there are moments when silence isn’t an option. Whether it’s standing up for fairness, supporting a friend, or choosing kindness in the face of disagreement, we all have the power to leave a meaningful impact through the principles we choose to uphold.

As we reflect on these quotes, we’re struck by how relevant Dr. King’s words remain. They inspire us to approach the world with more compassion, to act with intention, and to believe that even small, everyday choices can make a difference.

On this Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we hope his teachings inspire you as much as they inspire us. Let’s honor his legacy by carrying forward his ideals—not just today, but every day. Let’s find ways to connect, to uplift, and to act with the courage and love he so powerfully demonstrated.

On behalf of everyone here at Minich MacGregor Wealth Management, we wish you a meaningful and reflective day. May Dr. King’s vision inspire us all to keep building a brighter future together.