As financial advisors, we are big believers in checklists. They help us stay organized, keep our priorities straight, and ensure that everything we need to do for you gets done.

One of the items on our personal checklist this month is to send a checklist to you.

It’s 2024! A new year means new opportunities, new adventures, new goals to achieve. But doing all that requires some housekeeping. There are certain financial steps we highly recommend you take early in the year in order to make the rest of 2024 as enjoyable and stress-free as possible. So, to that end, we are including a short “Q1 Financial Checklist” with this letter.

The well-known surgeon Atul Gawande said in his book, The Checklist Manifesto: “Checklists cannot be lengthy. A rule of thumb is to keep it between five and nine items, which is the limit of working memory.”With that in mind, we’ve chosen seven items that are especially important.

The tasks on this list are all things that should be taken care of in the first quarter. Don’t worry – they’re not difficult! In fact, you may have handled most of them already. Some may not even apply to you. But each task is important in its own way. Put them all together, and you will find yourself more financially organized…and several steps closer to your financial goals.

If you need help or have questions about any of these, please let us know. In the meantime, we hope you have a great first quarter…and a wonderful 2024!

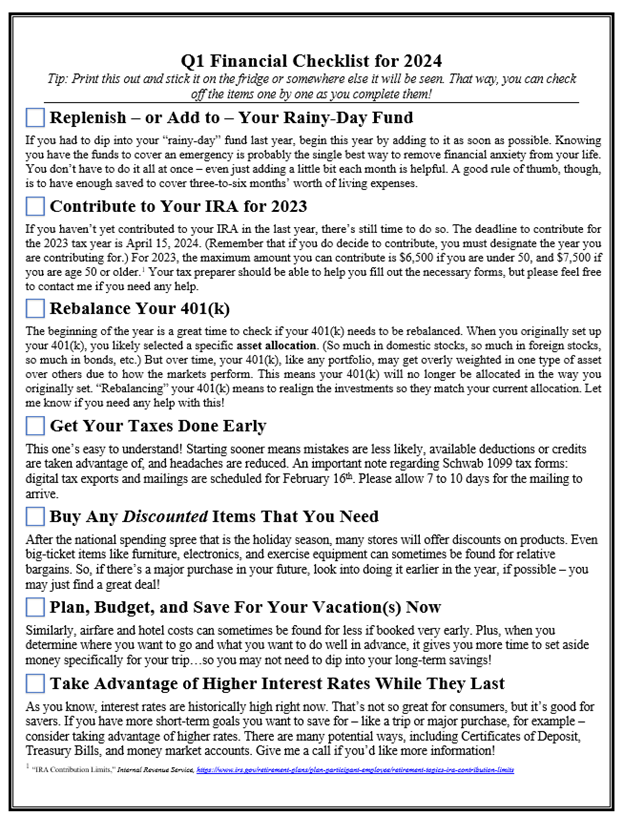

Q1 Financial Checklist for 2024

Tip: Print this out and stick it on the fridge or somewhere else it will be seen. That way, you can check off the items one by one as you complete them!

Replenish – or Add to – Your Rainy-Day Fund

If you had to dip into your “rainy-day” fund last year, begin this year by adding to it as soon as possible. Knowing you have the funds to cover an emergency is probably the single best way to remove financial anxiety from your life. You don’t have to do it all at once – even just adding a little bit each month is helpful. A good rule of thumb, though, is to have enough saved to cover three-to-six months’ worth of living expenses.

Contribute to Your IRA for 2023

If you haven’t yet contributed to your IRA in the last year, there’s still time to do so. The deadline to contribute for the 2023 tax year is April 15, 2024. (Remember that if you do decide to contribute, you must designate the year you are contributing for.) For 2023, the maximum amount you can contribute is $6,500 if you are under 50, and $7,500 if you are age 50 or older.1 Your tax preparer should be able to help you fill out the necessary forms, but please feel free to contact me if you need any help.

Rebalance Your 401(k)

The beginning of the year is a great time to check if your 401(k) needs to be rebalanced. When you originally set up your 401(k), you likely selected a specific asset allocation. (So much in domestic stocks, so much in foreign stocks, so much in bonds, etc.) But over time, your 401(k), like any portfolio, may get overly weighted in one type of asset over others due to how the markets perform. This means your 401(k) will no longer be allocated in the way you originally set. “Rebalancing” your 401(k) means to realign the investments so they match your current allocation. Let me know if you need any help with this!

Get Your Taxes Done Early

This one’s easy to understand! Starting sooner means mistakes are less likely, available deductions or credits are taken advantage of, and headaches are reduced. An important note regarding Schwab 1099 tax forms: digital tax exports and mailings are scheduled for February 16th. Please allow 7 to 10 days for the mailing to arrive.

Buy Any Discounted Items That You Need

After the national spending spree that is the holiday season, many stores will offer discounts on products. Even big-ticket items like furniture, electronics, and exercise equipment can sometimes be found for relative bargains. So, if there’s a major purchase in your future, look into doing it earlier in the year, if possible – you may just find a great deal!

Plan, Budget, and Save For Your Vacation(s) Now

Similarly, airfare and hotel costs can sometimes be found for less if booked very early. Plus, when you determine where you want to go and what you want to do well in advance, it gives you more time to set aside money specifically for your trip…so you may not need to dip into your long-term savings!

Take Advantage of Higher Interest Rates While They Last

As you know, interest rates are historically high right now. That’s not so great for consumers, but it’s good for savers. If you have more short-term goals you want to save for – like a trip or major purchase, for example – consider taking advantage of higher rates. There are many potential ways, including Certificates of Deposit, Treasury Bills, and money market accounts. Give me a call if you’d like more information!

[1] “IRA Contribution Limits,” Internal Revenue Service, https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-ira-contribution-limits